THE economic crisis caused by the COVID-19 pandemic will have a lasting impact on Canada’s economic performance and government revenues, new research from The Conference Board of Canada has found.

Profits and labour income, which are the main sources of revenue for the federal, provincial, and territorial governments, has been hard hit by the pandemic, according to The Conference Board of Canada. And it could take years for government revenue sources to recover to their pre-pandemic growth paths.

“Policy-makers must start planning now for the longer-term fallout from the pandemic,” said Pedro Antunes, Chief Economist at The Conference Board of Canada, on Thursday. “That means first stabilizing and then reducing the aggregate public debt-to-GDP ratio to enable the country to get through the next crisis or recession when it comes.”

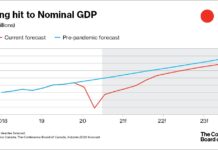

The COVID-19 pandemic led to the largest economic contraction in Canadian history. At its trough in April 2020, real gross domestic product (GDP) was at 82 per cent of its February (pre-COVID) level, a total of three million Canadians were out of work, and total hours worked had plummeted 28 per cent.

In its November fiscal update, the federal government tallied up the costs of its COVID-19 relief measures. The result is that the deficit will swell to $385 billion in 2020–21. The provinces and territories have also tallied record deficits—$92 billion, on aggregate. Taken together, the fiscal gap will account for roughly 22 per cent of GDP this year.

Additionally, federal and provincial/territorial governments will see their total net debt rise to over 95 per cent of GDP after the pandemic has passed, levels last seen in the early 1990s when surging deficits led to a decade of fiscal restraint.

By 2030–31, the provinces and territories will see their net debt-to-GDP ratio top 53 per cent, in line with that of the federal government and pushing the aggregate net debt‑to‑GDP ratio to well above 100 per cent.

“Low interest rates will help the federal government manage its debt load, but the situation for the provinces is bleaker,” said Antunes, adding: “Our longer‑term perspective suggests that, on aggregate, the situation for provinces and territories is untenable.”

The lasting impact on revenues and expenditures suggests that governments in Canada will struggle over the near and longer terms to dig themselves out of this fiscal hole. From fiscal year 2020–21 to 2023–24, the federal and provincial/territorial governments are expected to add $940 billion to the aggregate net debt. This will bring aggregate net debt as a share of GDP to over 95 per cent, a level not seen since the early 1990s.

The Conference Board of Canada’s outlook for modest economic growth suggests that the federal and aggregate provincial/territorial governments will not be able to rein in their deficits without additional revenue measures or cuts to spending.

Complicating matters, provinces and territories will look for additional health transfers from the federal government in coming years to cope with their aging populations. The federal government will not be able to meet these demands without introducing additional revenue measures.

“Once the current crisis has passed, tax increases, spending restraint, or a combination of the two are the only viable solutions going forward,” said Antunes. “Absent such initiatives, the provinces and territories will be forced to raise their taxes or make unpopular reductions in programs.”