ALTHOUGH only a few households in Metro Vancouver have a water meter, the political will for mandatory metering is strong, new survey results suggest.

Jordi Honey-Rosés, associate professor in the school of community and regional planning at UBC and Pascal Volker, a master’s student, surveyed elected councillors and mayors in the region and found that 68 per cent support mandatory water metering.

In this Q&A, they explain what their findings could mean for future water conservation in the region.

Why are water meters important?

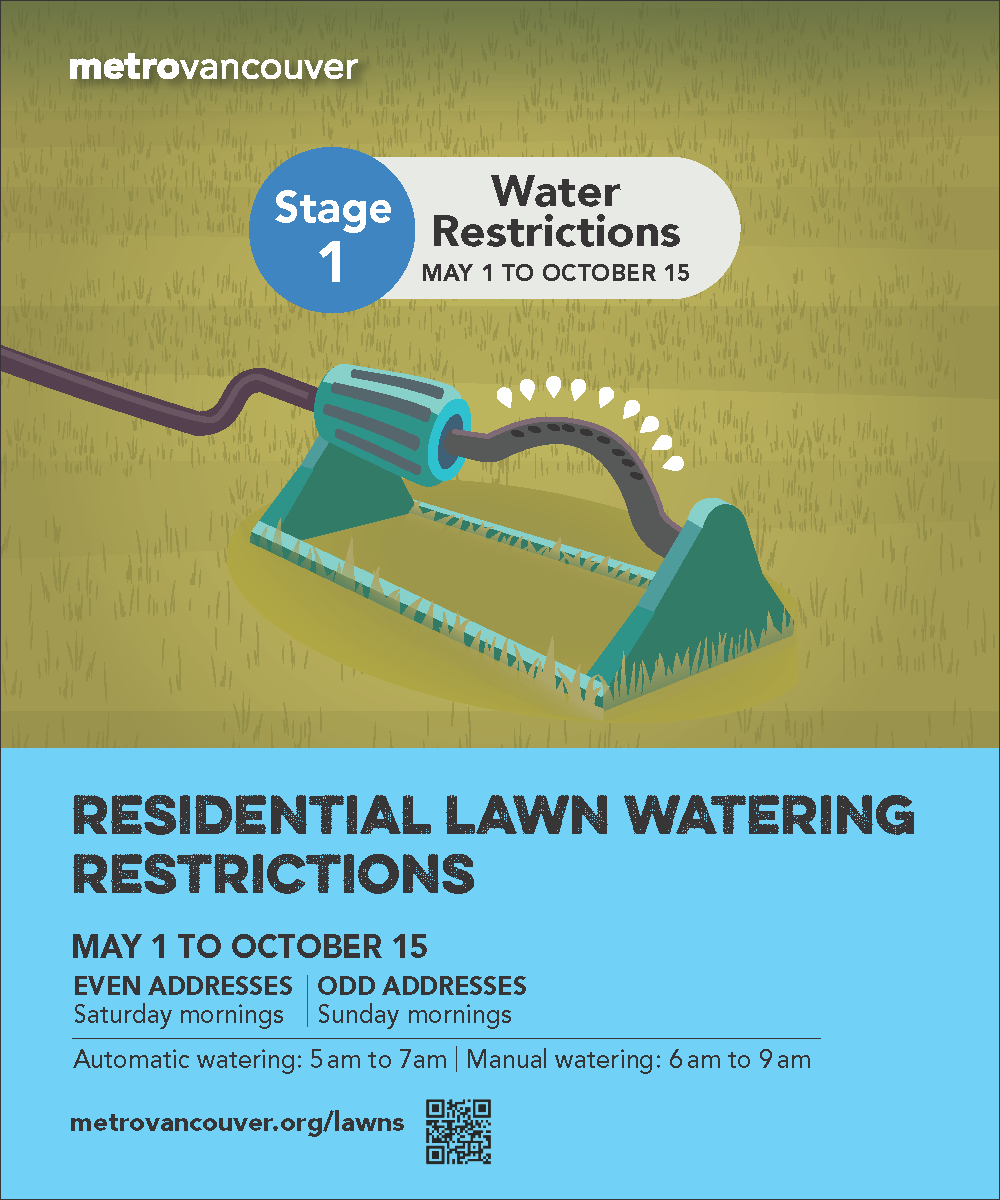

Pascal Volker: Water meters track household water use and help detect leaks, develop fair rate structures, and promote smart water use. They allow cities to identify consumption habits by different social groups. Municipalities that install water meters tend to consume much less water and can develop policies based on accurate data. In Vancouver, we pride ourselves as being environmentally conscious, and yet we use much more water than most other major cities, even those with comparable climates, like Seattle.

Jordi Honey-Rosés: While Victoria and West Vancouver have been able to provide a water meter to nearly all residents, much of B.C. and many cities in Metro Vancouver are far behind national coverage rates. Most cities have no water metering policy and have been hesitant to introduce water meters. We need to understand why this is so—and elected officials’ attitudes and beliefs towards metering is one of the main pieces in the puzzle.

What did your survey find?

PV: Results showed that 68 per cent of city councillors support mandatory metering. Around 80 per cent agree that water metering produces valuable information for city managers and is an efficient tool for sustainability. A big majority—73 per cent—are in favour of exploring the benefits of water metering in their city. Notably, this percentage is even higher among participants that are undecided about water metering.

Not surprisingly, support for metering is especially high in cities that already have mandatory or semi-mandatory policies. In municipalities where there is currently no metering policy in place, support for metering drops. But at the same time, even in cities that currently do not have water meters, there are council members who are in favour of mandatory metering, suggesting that there may be champions for this policy.

JHR: We were also surprised to see that the argument about water meters being able to help create more fair rate structures did not resonate with our city leaders. The absence of water meters creates unfair rate structures in which everyone pays the same regardless of how much they use. The grandmother living alone pays the same as the large family, regardless of actual water use. Meters can help cities bill users for real use. But undecided council members were much more captivated by the arguments about the value of the data being collected with this technology.

How do you see your findings being used?

PV: Water metering is not high on the political agenda, and so there is limited information on how city councils view the matter. We hope the results of this survey can help empower municipal planners, engineers and staff who agree that metering is a smart way to improve water management, but who might have hesitated to take this issue to council. This survey also highlights the importance of addressing legitimate concerns, such as access to water as a human right, associated costs and data management, in any planned rollout of metering.

JHR: One of the key takeaways is that there appears to be the political will for exploring and implementing water meters in Metro Vancouver. With the results of this survey, it is hard to argue that Metro Vancouver has low metering coverage because of the lack of political will. It seems that the time has come to embrace metering technologies that can help us be better stewards of our water resources.