HOSPITALIZED patients are more complex than they used to be.

That’s the finding of a newly published UBC study which set out to measure something researchers have been hearing anecdotally from hospital-based health-care workers over the past two decades.

As it turns out, they weren’t imagining things.

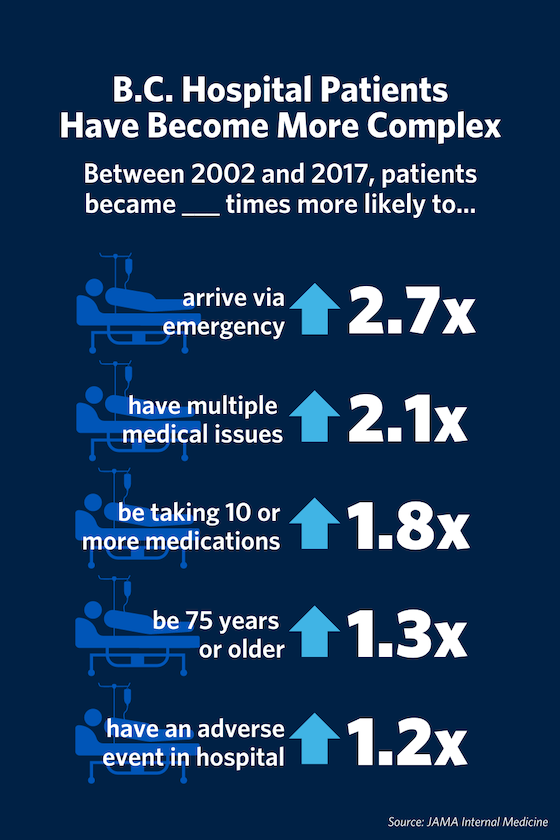

An analysis of administrative health data covering 3.4 million non-elective hospitalizations in B.C. between 2002 and 2017 revealed that by the end of this 15-year period, patients were more likely to:

- be 75 years or older

- have multiple medical issues

- rely on multiple medications

- be admitted via the emergency department

- suffer an adverse event while in hospital

- require an unplanned readmission to hospital within 30 days of discharge

The study period concluded before the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, so the effect of the pandemic on these trends has not yet been measured.

“This study isn’t just about numbers. It’s about real people with increasingly complex health needs,” said the study’s first author Dr. Hiten Naik, a research fellow with the UBC faculty of medicine’s Clinician Investigator Program. “These trends highlight how important it is for health-care systems to evolve to meet the changing needs of not only patients, but also the health professionals who treat and care for them.”

The increasing complexity of patients isn’t necessarily leading to more serious outcomes for them. In fact, they have become less likely to die while in hospital, or be admitted to intensive care. This suggests the health system is adapting well to their needs.

Other metrics in this category such as prolonged hospital stays and unplanned readmissions increased slightly but not nearly to the degree that patient complexity did.

“The rates of these negative outcomes remained relatively steady in comparison to the patient characteristics of complexity, so you could say the health system kept up,” noted Naik. “But this kind of adaptation isn’t automatic. The trends suggest that patient complexity will continue to increase.”

The researchers stressed the need for governments to be proactive to ensure that complex patients get the kind of care they need—now and into the future.

The study was published on Monday in JAMA Internal Medicine.